Episode 123: Holocaust Education

Alan Marcus is a professor in UConn’s Neag School of Education and among his areas of focus is global education with an emphasis on the Holocaust and teaching difficult history. Last year, he led a program at E.O. Smith High School in Storrs that Taught lessons about the Holocaust and larger issues of identity. The program, which was also offered to local members of the community, consisted of interactive experiences with Holocaust survivors, a virtual tour of a Holocaust concentration camp, and a photography exhibit featuring E.O. Smith teachers and staff members in their life way from school. Marcus talks about how social media has affected the way the Holocaust is thought of in these times and what the future of this program might be.

Link to Episode 123 at Podbean

Transcript

Mike: Hello everybody. And welcome again to another episode of the UConn 360 podcast. It’s October and the fall semester is rolling along here at UConn We’re happy to have a very important guest with us today. He’s Alan Marcus, a professor in the Neag School of Education, working with curriculum and instruction. His scholarship and teaching focuses on museum education, teaching with film, and global education with an emphasis on the Holocaust and teaching difficult history.

He earned his undergraduate degree from Tufts, got advanced degrees from BU and Stanford. He recently developed a program at nearby E. O. Smith High School, go Panthers, called Breaking Bias and Creating Community. He’s going to tell us a little bit about it in his answers, but it involved testimony from Holocaust survivors, a virtual reality tour of the Auschwitz concentration camp and interestingly, a photo exhibit that focuses on issues of identity with local communities members today. And he hopes to bring that program to other high schools in the state. Just a little funding. That’s all that’s needed. Alan, thanks for joining us today.

Alan: Thanks so much for having me. Great to be here.

Mike: It’s great to have you. Tell us a little bit about your background and how Holocaust education became so important to you.

Alan: So I was a high school teacher for seven years in Georgia before going into higher education. And I always was intrigued by teaching what we call difficult history, topics that were challenging to teach in some ways. And I found that my students were most engaged around those topics. We looked at multiple perspectives on different issues. They thought about the difficult decisions that human beings had to make. And the Holocaust was one of those.

And I found it was particularly challenging to teach the Holocaust. And so that actually was a motivation to me. To be teaching it and to be teaching it well. When I came to higher education and I was doing my own research in K 12 schools, I actually initially avoided Holocaust education as part of what I was doing.

And in part because it was so challenging and in part being Jewish, it sort of hit close to home, and the emotional engagement that it takes to engage with teaching the Holocaust is. It’s difficult. And it took me a good seven, eight years before I finally circled back to that as a real passion.

I was motivated by having survivors come speak to my students here at UConn. And so hearing their stories and realizing, no, I really need to do this. And I’ve been working with the Holocaust Museum in D.C. and in Illinois and other places. And so that’s sort of how I came to, to focus on the Holocaust.

Izzy: Well, UConn is sure happy to have you. So, the Holocaust, along with antisemitism in general, seems to be in common use with the advent of social media and the internet. Why do you think that is?

Alan: Well, antisemitism has been around for thousands of years. The Jews were blamed for the the Black Plague during the Middle Ages at different points in time, they were evicted from England and France and Spain which is why so many ended up in Eastern Europe.

And of course they were targeted during the Holocaust. Antisemitism has been here, but social media has just made it easier for people to spread their views and to reach so many other people. You know, the algorithms on social media help focus what people see. And so if they start looking at hatred that’s online, they’re going to keep getting those feed.

I think with the advent of social AI, artificial intelligence, it’s so easy to manipulate images and video and audio to make things up and we don’t do a good enough job in K through 12 education at helping students be more media literate.

So antisemitism has always been there. It’s now just more accessible for people to see and anyone can post anything online and make things up. And we need to do a better job at helping students understand what’s coming through their social media feeds, and how they perhaps need to be a little more critical of what they’re seeing.

Mike: Tell us a little bit about the program you helped bring to E.O. Smith. It seemed to emphasize both Holocaust education, but also bias education and the biases that exist here today in 2024.

Alan: Yeah. So let me start with the biases that exist here today. You know The Anti Defamation League, the ADL, has been tracking hate crimes and online hate for decades.

And the past several years have been the highest numbers of antisemitic and racist incidents since they began. We’re tracking in Connecticut in 2022 the ADL showed 100 percent increase in antisemitic incidents in Connecticut versus only a 36 percent increase nationwide, which in and of itself is high last year, one third of the antisemitic incidents in Connecticut were in K through 12 schools. that were recorded. And if you look at the, the social media piece 17 percent of TikTok content related to the Holocaust either denied or distorted it. And 20 percent of Holocaust related posts on Twitter, now X, did the same thing, denied or distorted it. So we’ve seen this really worrisome trend and as a result, there are a number of people, including myself, who believe it’s important to be getting into K to 12 schools and working with teachers and students.

So, this project initially was done by Common Circles. which is a non-profit in the New York area, and they were working with the White Plains Public Schools, and they brought me in to, to help with that project. I then brought the project to E.O., and we made you know, a few changes. So, essentially, we’re looking to increase empathy decrease bias, and build community.

That’s the essence of what we’re trying to do. We did that at through three we call them sort of exhibits but three components to this project. The first one is a photo exhibit where we had members of the community, including teachers, administrators, and other members of the community not in the school, who posed for photos.

And those photos showed five aspects of their identity. It was in the main hallway and students would come in over the course of a couple months and see these photos and realize they might only know people on the surface. And they might only know some things that they see and there’s other layers to people’s identity.

And that identity is a really important way we were helping people think about bias. The second part is called The Journey Back.

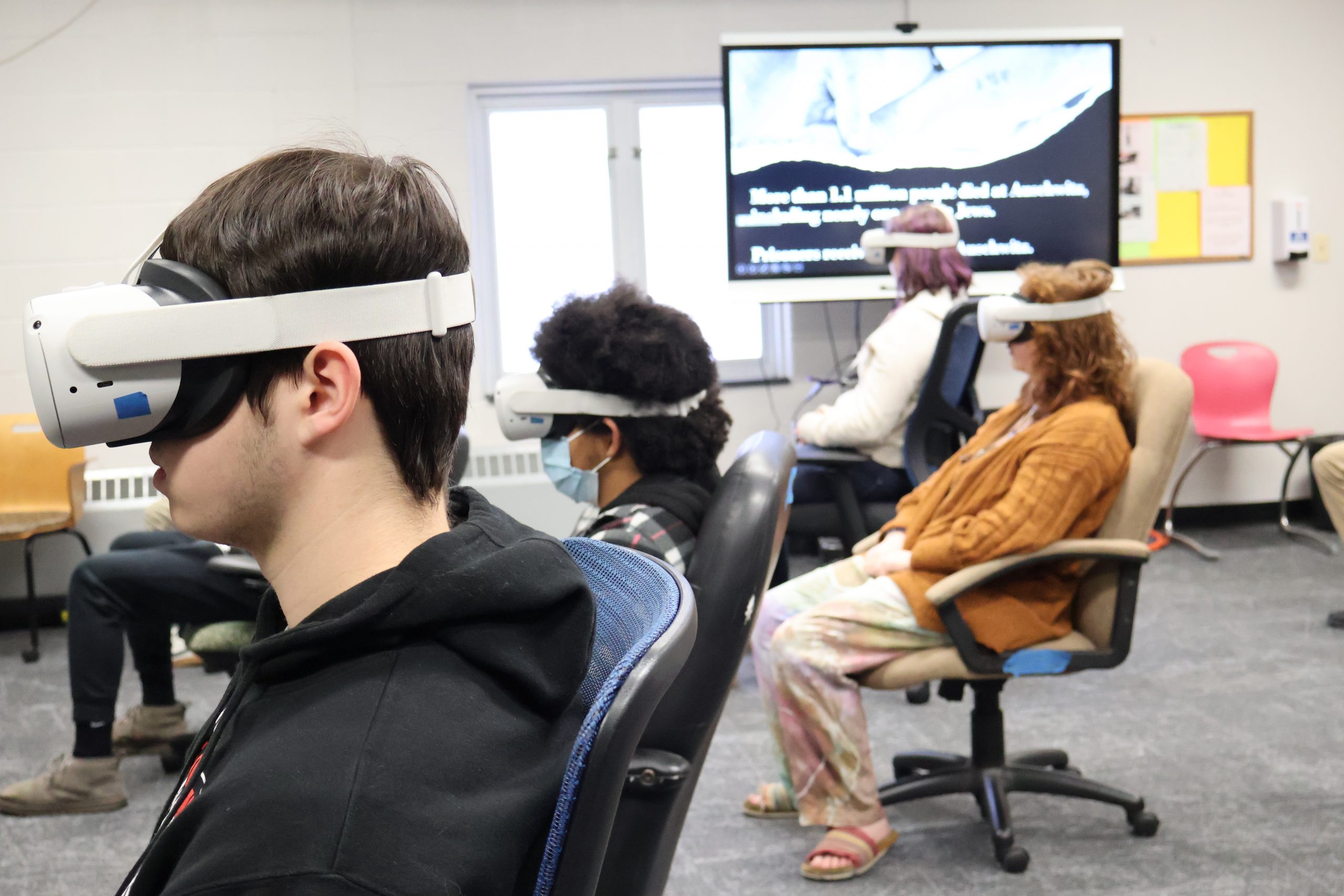

The Journey Back is a virtual reality experience that was done by the Illinois Holocaust Museum. It’s in their museum and they are now starting to send out headsets to schools. It’s virtual reality. It’s a tour given by a survivor of Auschwitz and talks about their experiences and also hits on important issues.

The third component that we brought to the school is Eyewitness, which are digital, interactive Holocaust survivors put together by the USC Shoah Foundation and it was originally founded by Steven Spielberg, and they have several survivors, and they, they were filmed over the course of a week, asked thousands of questions, and you can actually have a real live like live conversation with them.

So we had these three components. We had over 700 students out of 1.100 students at E.O. that participated in the project. It was interdisciplinary. It was, it included the English department, the Social Studies department, the Art department, as well as the choir that participated. And it, it was going so well that teachers at the school decided they wanted to extend it.

So they ended up a month later having a week long teach in where they invited about 20 speakers over the course of a week to come into the school and talk about issues of bias and racism and antsemitism and building community. We also held a community event. We held an open house. We had parents and members of the community come in.

That was very successful. We had an event for UConn students and professors. We had students that were involved in the Human Rights program and the Digital Media Design program came in. We ran professional development for teachers and finally we had our research component. We were collecting data to see is what we’re doing making a difference.

Mike: I did the virtual reality part of the experience for a story I did for UConn Today and it was just you know, the technology, that virtual reality is and how it allowed you to, you felt like you were there. I mean it affected me and I’ve got to believe it affected anybody who took part in that exercise.

Alan: So one of the first people who saw it was the superintendent of schools. So we had a day when it was set up. We invited all the staff to come see it first, right? You wouldn’t want a teacher to show something to their kids that that they hadn’t seen. And the superintendent comes in and like many of the adults who came in was very emotional.

And she left and she said, first thing I’m doing right now is I’m going to find the custodians and they’re going to bring you a box. a box of boxes of tissues so that you have tissues for the next month because a lot of people are going to need them.

Izzy: How were some of your students involved in this project?

Alan: One of the, my core roles at UConn is running the secondary history education program. And our teacher education program really values the experience that our pre-service teachers get in school. So after student teaching, they come back for a year.

One of the only programs in the state that does that. They do internships. And these internships are designed to help them build leadership skills, work on curriculum, do things besides just what they do in the classroom. So we were able to create an internship. for this project. So we had three interns pre service teachers from the, the Neag School, and they worked on the project all year.

They helped run professional development with teachers, they helped design lesson plans to go with these different aspects of the project, and they were trained as docents. So, while I was working with E.O. students running the virtual reality, our UConn interns were the ones that were running the discussions with the digital survivors.

And that takes a lot of skill. You have to know the survivors and what they’re going to be saying ahead of time. You have to help get questions out of the students. Sometimes you have to redirect or reword questions. So the interns did an absolutely fantastic job. And then they ended up staying and helping with the teaching as well.

So. It was, it was a really, I think, powerful experience for them.

Mike: You got into it a little bit, Alan, but, but talk a little bit about how the high school students reacted. I mean, you’re talking about you know, E. O. Smith High School here in Eastern Connecticut, which, you know, there’s a wide variety of students that attend and with different upbringings and different attitudes. What was it like working with the high school students?

Alan: Well, one of the reasons we chose E. O. Smith is in part because it’s right here and has connections with the university, but in part because it’s such a unique community and building community was an important part of the project.

So it’s a regional school. So, it has students that come from many different towns in the area and there’s a large diversity in terms of socioeconomic background as well as ideological beliefs. We also have a lot of students who are kids of faculty so it was a really unique environment to try to build community.

I mean, you get all these freshmen coming from all these different middle schools who’ve never met each other. So that part was really important. The response was overwhelmingly positive in terms of, of how the students responded and the teachers as well. So we actually did surveys with every student who did both the virtual survivor piece and the virtual reality and trying to get a sense of the students and their reactions.

Students overwhelmingly said they better understood the Holocaust. They said that a, they believed it was important to study bias and learn about the Holocaust. They felt like they’d had a real conversation with the survivor. They knew the survivor wasn’t there. We weren’t trying to fool them, but they said they got so caught up in and having this conversation that they forgot the person wasn’t, you know, live on a, on a Zoom call.

We interviewed students as well after their experiences. The students also said it was very emotionally powerful and they indicated they were developing empathy. That they were connecting with these survivors in a way that I think they wouldn’t do from hearing a lecture. They wouldn’t do from reading a textbook.

So that was really positive. And we also interviewed teachers who participated. Every single one said this was a very positive experience with their students. There were teachers who said they’ve never seen their kids engaged like this with any other type of activity. There was one teacher who said it was the only time in years he has ever seen every single one of his students sort of paying attention and engaged with what they were doing.

The principal said he expected perhaps some pushback from some members of the community given we were dealing with issues of bias and racism, et cetera. He said he didn’t have a single negative reaction from a parent, but did receive lots of emails with positive reactions from parents, including people saying we really applaud the school taking on these difficult issues and bringing in the community.

So both in terms of, you know, anecdotal data as well as formal research we think it’s been a very positive experience. One of the challenges for Holocaust education is how do you measure long term effects, right? Because in the long term, you’re trying to change people’s behaviors as individuals.

So that’s one of the challenges is how do we look at this long term and can we come back and interview kids in two or three or four or ten years to see what the impact might have been.

Mike: It’s pretty impactful. Impactful subject and talk a little bit about, and it’s great that you brought it to the community because in general we’re always trying to work on town-gown relationships here at UConn. But what was it like bringing people in from Mansfield and some of the other surrounding towns?

Izzy: Yeah, I’d love to know some of people’s reactions outside of the school system.

Alan: Yeah, you never know what you’re going to get in terms of people showing up for a community event and wanting to participate. But it, it seems that if we were trying to build the E.O. Smith community, it would be artificial to only include the students. The community is broader than, than just the people at the school, especially that given that it was multiple towns. So we had sent out emails to all the parents, we contacted local businesses, we contacted local religious organizations, and we had we were hoping to get 60 people. We had 90 people RSVP and we had 120 people show up. One of the ways that E.O. students were also involved is they got trained to lead the discussions at this community event. So members of the community came in, they got to experience these different parts of the project, and then they were put in small groups. We had rabbis there. We had Greg Haddod, our local state representative. We had lots of parents of kids other members of the community members of the Board of Education, and they participated in these small group conversations around what do we, what is our community? What do we think it is? What does it mean to us?

Where do we want it to go? How do we build community? And there were E.O. students that led these conversations. So I think that was very powerful. We had local businesses and individuals contribute funds to make this project possible. It was not inexpensive and the, again, reaction from the adults, they were blown away, I think, by the technology it was a very powerful experience for them, I think and the feedback was, again, was very, very positive.

Izzy: It sounds like this project has already been incredibly successful, but where do you think it’ll take you next?

Alan: Well our goal is to get this into lots of schools in Connecticut. You know, we’re starting small, so we’re looking at two or three schools the next year or so, and then maybe expanding to five or six or seven or eight.

The key is to make it sustainable. I was on sabbatical last semester. I was able to be at the school full time. Working along with my interns, but our goal moving forward is to be able to go into a school, work with teachers in the summer, train teachers to be the docents for these different experiences.

Still have student interns involved for the, when it’s schools that are in the area. But it’s also important to customize this. for each school. So the photo exhibit needs to be redone every time, because it’s got to be members of their community. And we also want to work with the school to, to find out what are they doing in their curriculum, what are their goals, to make the project fit in with their goals.

It’s not just us coming in saying, here’s what you need to do. You’ve got to work with the school and the context of that school and who their students are. You might do very different things in West Hartford than you might. You know, a few miles away in Hartford. So our, our goal then is to work with schools, customize the experience for them, make it sustainable.

Part of that, of course, is raising funds. So working with my dean and the UConn Foundation. We’re looking to raise enough money to do things like buy our own VR headsets. We can only get them for a few weeks from the museum, so if we have our own, we can rotate them to schools all year long you know, and to, to help fund other aspects of the project.

Mike: Alan, this is really great work you’re doing for UConn, great work you’re doing for the community, It’s got to be very rewarding for you.

Alan: It is but it is also as I said, challenging to constantly be listening to stories of the Holocaust. And you know, ultimately it comes down to these, really difficult things that people went through and difficult decisions people had to make.

Parents had to decide, do I send my kid away in hopes of them surviving, but I never see them again.? Do I do work at a camp that I know is helping the Nazi effort, but it’s keeping me keeping me alive? So it’s difficult work. It’s also important to note that we have new K through 12 social studies standards for the state of Connecticut. I’m a little biased because I was one, one of their, the writers for those but they Holocaust education and ant bias education is, is an important part of what’s there. We also are one of only a handful of states that require Holocaust education. It’s state law in Connecticut that you have to teach the Holocaust. So we’re trying to build on the good work that the state of Connecticut does as well.

Mike: I have one more question for you. Obviously, we hope that people listen to the UConn 360 podcast from all over the world, or at least all over the country. But if somebody is sitting there listening to our podcast and does not have access to what you provide to the students, what would you recommend for them to do to learn and be educated on the Holocaust?

Alan: One of the best places to start are the various Holocaust museums that are out there. They have incredible education materials. So, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D. C., the Illinois Holocaust Museum you know, any region of the country you’re in, there is a Holocaust Museum. Houston and Dallas and Texas two in LA, San Francisco so whether it’s a local one or you’re, you’re borrowing materials online regionally, that’s a great place to start. They have information on content they have lesson plans another organization that puts out wonderful materials is Facing History and Ourselves, they’re based out of Boston, I believe, but they, their materials are online, the eyewitness interactive digital holocaust survivors that we use are available online. That was not something that was just available to us. And so you can go on there and use those. My recommendation is it takes some, some time and effort and training to do that well. But that’s another great resource.

And then I’ll give one other source. There’s a great book by Doris Bergen called Concise History of the Holocaust which is, I actually have my students read that as well. That’s a great place to start if you’re, if you feel like you don’t know a lot about the Holocaust.

Mike: Well, Alan, we’re really grateful for your work and, and all you do for UConn and we’re grateful that you stopped by today to talk to us at the UConn 360 Podcast

Alan: Thanks for having me.

Mike: Thank you everyone for listening and we hope you join us again for the next UConn 360 podcast.